Brexit: a “moving target” for the Swiss business sector too

- Introduction Executive summary | Positions of economiesuisse

- Chapter 1 Mixed picture for trade after Brexit

- Chapter 2 Brexit – status of the withdrawal process

- Chapter 3 Ongoing uncertainty for Swiss companies

- Chapter 4 Potential risks for businesses

- Chapter 5 Political priorities from the point of view of the Swiss business sector

Brexit – status of the withdrawal process

After Prime Minister Theresa May formally notified the EU in March 2017 about the UK’s withdrawal from the Union, the initial negotiations focused on three main areas:

- the rights of British citizens in the EU and vice versa

- the UK’s financial obligations towards the EU

- regulation of the national border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

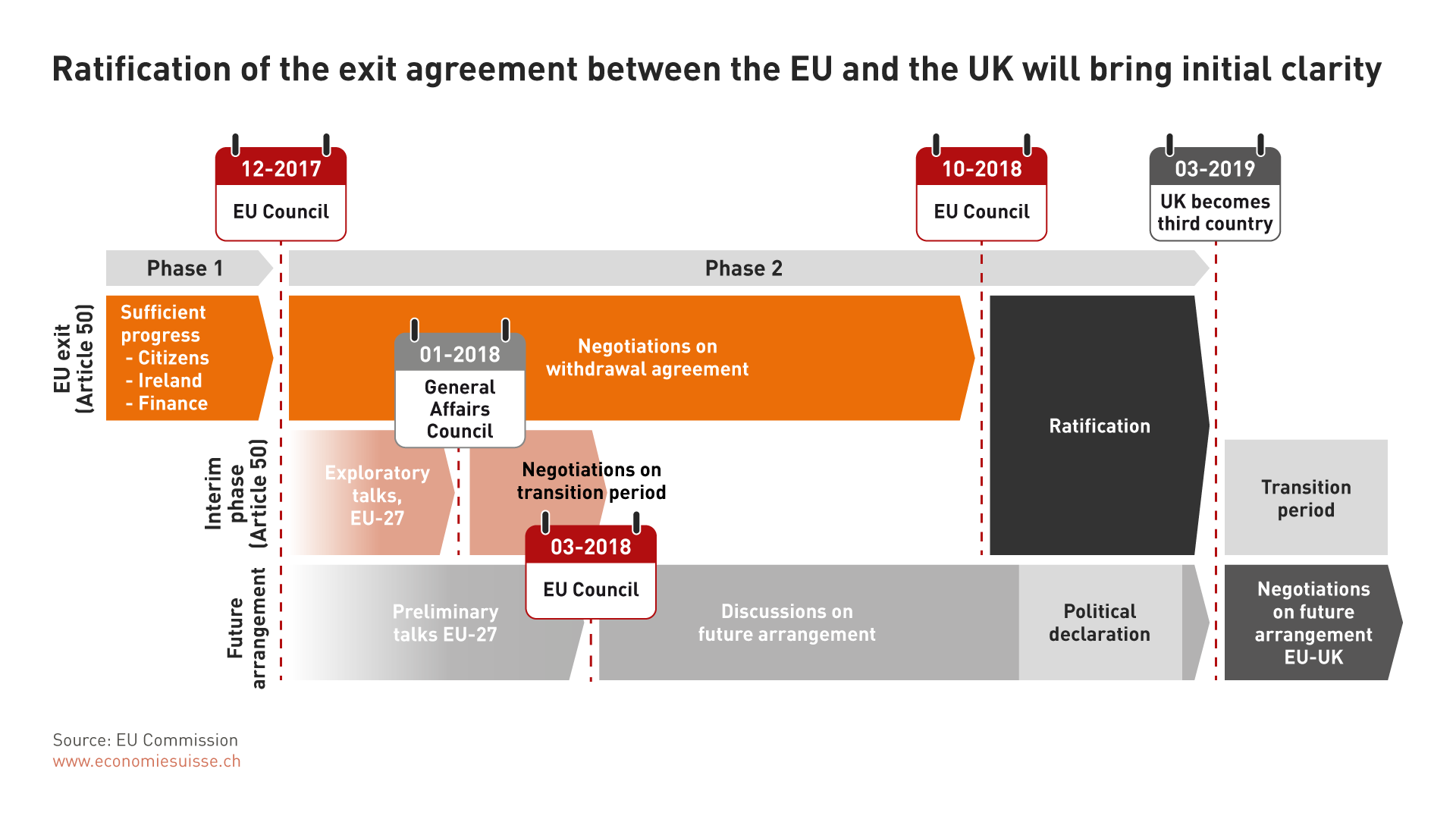

Although the parties had been unable to reach agreement on all points, on 15 December 2017 the EU announced that sufficient progress had been made in the negotiations to permit the initiation of the second phase. In the first quarter of 2018, the aims were firstly to continue the exit negotiations, secondly to reach agreement on a transitional period to follow the actual Brexit date (29 March 2019), and thirdly to specify the initial main parameters of the future relationship. The timetable is already extremely tight on paper and if any delays or blocks in the talks should occur in the next few weeks (for example, regarding the problem of the Irish border) this would additionally hamper the ability to reach an agreement by the specified deadline.

Transitional period – “nothing is agreed until everything is agreed”

Adopted at the meeting of the EU Council on 23 March 2018, the UK and the EU reached agreement on some of the central points of the transitional period, which will commence on 30 March 2019 and end on 31 December 2020. During this period, the UK is to remain in the single market and the customs union and will also have to continue paying the same membership contributions. Also, during the transitional period, the European Court of Justice will be responsible for settling disputes, instead of the British Supreme Court. Furthermore, the UK will in general no longer be able to participate in the decision-making process.

All the UK’s rights and obligations towards third countries will also remain in place during this period. The UK will be able to negotiate, sign and ratify trade agreements with other countries during the transitional period, but these can only enter into effect after the transitional period is over. This also applies to agreements with Switzerland. This means that the UK will be able to initiate formal negotiations on its future relations with Switzerland as of 30 March 2019.

All of this is based on the strong provison that the foreseen transitional period becomes part of the definitive exit agreement between the UK and the EU. This means that “nothing is agreed until everything is agreed”. For instance, the issues relating to the settlement of disputes and the border between the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland still have to be resolved and could therefore prove to be major obstacles. At the end of the process, the exit agreement will have to be formally ratified by the EU Council as well as the parliaments of the UK and the European Union. The agreement will have to be concluded by October 2018 in order to allow sufficient time for its ratification by 29 March 2019. In addition, bilateral agreements between the UK and third countries will be necessary to ensure that the existing agreements between them can also be maintained during the transitional period. Until these are in place, the business sector will not be able to count on binding framework conditions post-Brexit.

Figure 4

In view of the complex tasks involved, unresolved issues and enormous time pressure, it is still uncertain whether it will be possible to reach an agreement by the specified deadline. Thus, an unregulated exit by the UK from the EU is still a possible worst-case scenario.

Lack of clarity regarding the future relationship between the EU and the UK

The picture with respect to the future relationship between the EU and the UK is even less clear. Initial parameters are to be defined by the end of 2018 in the form of a political declaration and negotiated in detail during the transitional period. A variety of ideas for this have been put forward. The EU published an initial draft of its corresponding guidelines on 7 March 2018, according to which, given the red lines set down by the UK government (no jurisdiction of the European Court of Justice, autonomous trade policy, no free movement of persons, limited financial contribution, regulatory autonomy), only a comprehensive free trade policy would come into question, such as the one recently concluded with Canada (CETA). Access to the financial services market is to largely take place via equivalence mechanisms. However, a free trade agreement would mean reinstating customs procedures – a move that both parties want to avoid at all costs due to the problem of the internal border in Ireland. The EU has emphasised (with reference to Switzerland) that sector-specific agreements are not acceptable (cherry picking). However, the EU Parliament has signalled a certain degree of flexibility in areas such as civil aviation, fishery, research and innovation, energy and information and communication technology.

In her speech on 2 March 2018, Theresa May confirmed the UK’s exit from the EU single market and the customs union, but at the same time called for a comprehensive mutual recognition of standards (e.g. in the civil aviation and pharmaceuticals sectors). This, coupled with sector-specific arrangements and customs agreements, should permit as ambitious an agreement as possible to be reached that would minimise trade barriers and negative economic impacts.

Likelihood of new trade barriers

The potential solutions with respect to market access, regulatory convergence and formal requirements on cross-border trade are likely to give rise to a deterioration of economic relations between the UK and the EU, regardless of how the solutions are designed. However, it is difficult to make precise predictions concerning the impacts in the area of non-tariff-based trade barriers.

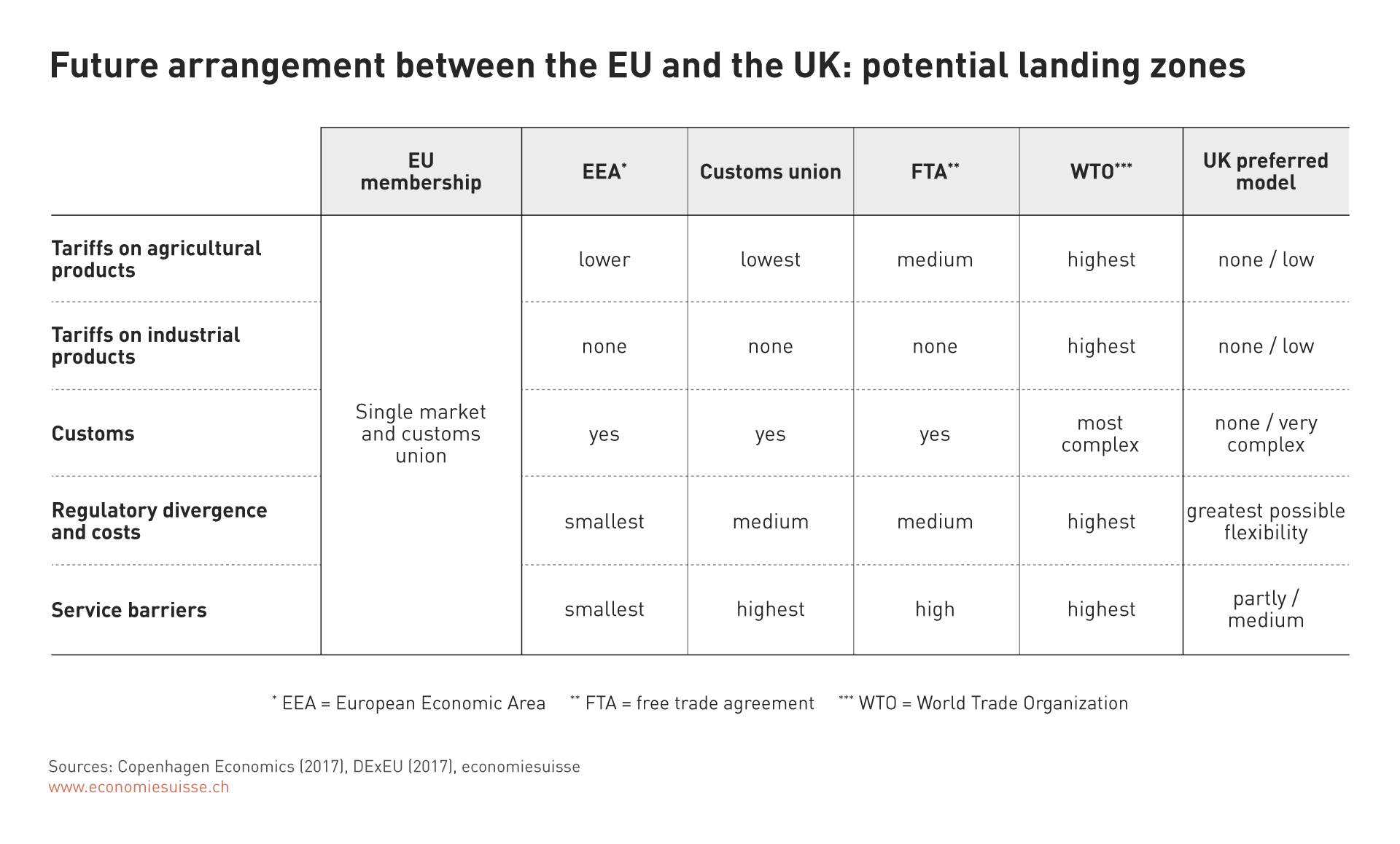

Table 2 provides a rough overview of the impacts to be anticipated with respect to customs tariffs, border controls and regulatory obstacles based on different models. In the event of a hard Brexit (regression to WTO rules), the negative consequences would in any case be the greatest (higher tariffs, comprehensive border controls, new obstacles to services and additional costs due to potentially divergent regulatory developments).

Table 2

EU united, British government under internal pressure

In the negotiations to date, the stances have differed on both sides, as well as the approach to the negotiations. The EU is currently demonstrating unity with respect to the main points. The European Commission, as well as the Parliament and the member states, are supporting the EU’s main demands on the UK (including no cherry-picked access to the single market, support for the interests of Ireland, clear financial demands on the UK, no right of co-determination during the transitional period). However, the possibility that in the course of the negotiations on the future relationship with the UK diverging interests on the part of some member states could play a role cannot be ruled out. This could give rise to a more pragmatic attitude, but also to new problems within the EU’s internal decision-making process.

By contrast, the UK’s Prime Minister is under a great deal of internal pressure, especially with respect to the position to be adopted for negotiating the future relationship with the EU. At present she has a very slim majority in the House of Commons, thanks to the support of the Democratic Unionist Party of Northern Ireland. At the same time, there are forces within her own Conservative Party and the Cabinet who are calling for a speedy and uncompromising exit from the EU. Recently the Labour Party has backed the demand by the UK business sector for a customs union with the EU. At least for the time being, though, it appears that options deviating from the position adopted by the government are unable to attract a sufficient majority in the UK Parliament.