Brexit and Switzerland

- Introduction Executive summary | Positions of economiesuisse

- Chapter 1 Brexit Is for Real

- Chapter 2 Great Britain and Europe at a Crossroads

- Chapter 3 Brexit and Switzerland

- Chapter 4 Business survey economiesuisse: Export Sectors Especially Affected

- Chapter 5 Safeguard Market Access, Ensure Legal Certainty, Seize Opportunities!

Great Britain and Europe at a Crossroads

A Difficult Reordering of Great Britain’s Multifarious Relations

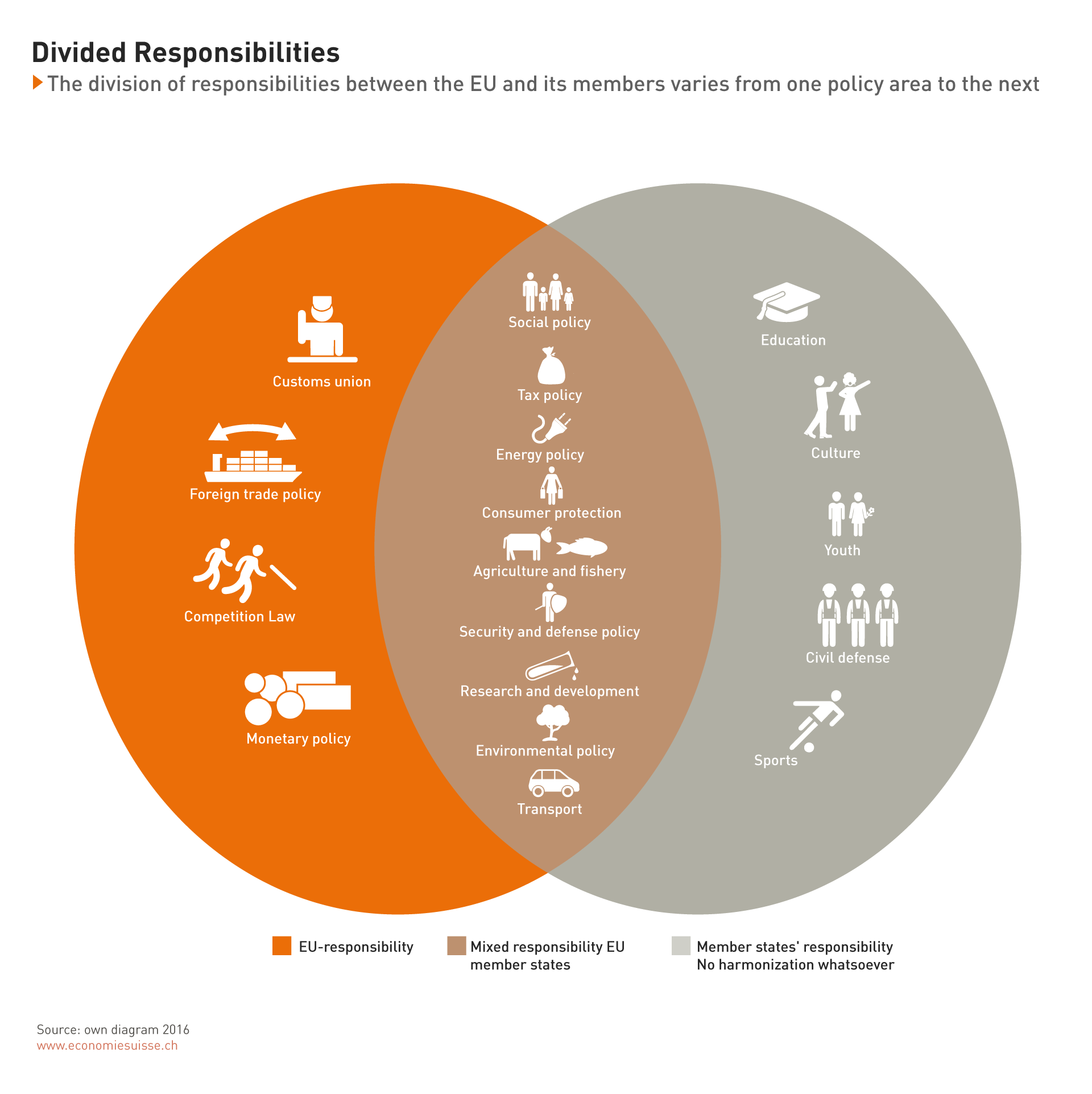

After the referendum of June 23, 2016, Great Britain faces the challenge of reordering a large part of its contractual relations with the rest of the world — most importantly, no doubt, the transformation of its ties to the EU. Closely tied by a complex assortment of partially shared competencies and large transfer payments the two parties now must extricate themselves from their mutual embrace. The European Union legal acts (acquis) currently include approximately 85,000 pages on trade, competition, and monetary policies (under EU-authority) and on shared responsibilities in agriculture and fisheries, transport, social policy, and the environment. In each of these areas, moreover, British regions and EU-member states have their own specific interests and priorities.

The EU acquis guarantees — e.g. in aviation — that member states have full access to each other without discrimination, but leaves the details (e.g. flight plans, slots) in the hands of the individual members states.

Chart 2

With Brexit Great Britain will have to dissolve its relations with the EU.

Most notable from the perspective of foreign trade is the EU states’ common trade policy as laid down in the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (Art. 207). Here the authority (e.g. for the conclusion of trade agreements) generally lies with the EU institutions. But — except as regards the goods trade — the authority of the EU is never absolute. The authority over services and intellectual property is divided, i.e. responsibilities are shared between the EU and the member states. Therefore, Great Britain will not be fully in charge of its trade policy until it has actually left the EU.

At that point, also a number of agricultural subsidies will no longer be forthcoming. Furthermore, a new stretch of external EU border will separate the Republic of Ireland from Northern Ireland and will have to be guarded accordingly. Great Britain will also have to re-introduce its own customs regime unless it joins the European Customs Union as a non-member state after Brexit. The UK also has substantial financial obligations to the EU—up to 60 billion pounds by to various estimates that it will have to fulfill even after it leaves the EU. They include multi-year pledges to the EU budget, pension fund contributions of the administration, and infrastructure projects.

Given the great number of fundamental economic policy issues that need to be considered during the withdrawal negotiations between the EU and Great Britain the available time frame seems very short. In the short term, therefore, temporary solutions (grandfathering) may be negotiated in some areas.

Brexit also Affects Relations to Third Countries

Great Britain’s exit will also have far-reaching consequences on its membership in international organizations and trade relations to important third countries. The EU currently has free trade or economic partnership agreements with over 50 countries, including Switzerland. More are being negotiated (e.g. Japan). They include many of Great Britain’s most important import and export partners.

By leaving the EU, Great Britain risks losing all the special conditions that the EU negotiated with non-member countries and from which British companies also benefit. The UK government must brace itself for a large number of negotiations if it wishes to maintain the favorable terms of access to the markets of important trading partners for its companies. In this context it has been announced that talks with several countries about a free trade accord are to be initiated shortly.

Questions Concerning WTO Membership

Another task awaits the United Kingdom — and possibly the EU as well — with regards to the WTO. While both the European Union and each of its (still 28) member states are independent members of the WTO, it is in fact the EU that negotiates obligations within the WTO on behalf of its members (e.g. customs tariffs, quotas, subsidy framework for agriculture) After leaving the EU, Great Britain will have to negotiate its own conditions of membership with the other 163 WTO members. In a first step, it may simply attempt to continue the obligations it had as a member of the EU. Any negotiated agreement will ultimately have to be approved by the WTO (with a two thirds majority of members) and the British Parliament. This process could be very contentious and might generate new demands and political pressure from other WTO members. Just as likely, however, the procedure might be drastically shortened if the UK seamlessly re-assumes its previous obligations. With no change in obligations there would be no need for negotiations.

For the EU, too, there is a certain risk that it will be pressured about its obligations as a result of Brexit. Article 62 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties contains language that refers to “a fundamental change of circumstances which has occurred with regard to those existing at the time of the conclusion of a treaty” (e.g. the loss of almost 18% of EU economic power) which might force the EU to adjust its obligations to other WTO members and possibly agree to further concessions. Just how bumpy the negotiations with the WTO will be for the EU and Great Britain is anybody’s guess.

Effects on Other International Organizations

In principal, other international organizations could also be affected in their membership structure by Brexit. However, since Great Britain is already a nation state member of the IMF, the World Bank and the OECD its exit from the EU has no impact on their respective decision making processes. For now it looks as though the institutional effects will be rather small.

It is conceivable that Great Britain will adjust some of its positions in multilateral bodies when it is no longer a member of the EU. At the IMF, the OECD, or the G20, Great Britain will soon be free to take a position independent of the EU. Just how far Great Britain will go in this respect will also depend on the shape of its new relationship to the EU. In other words, blowback from Brexit may end up affecting international cooperation at important international organizations.

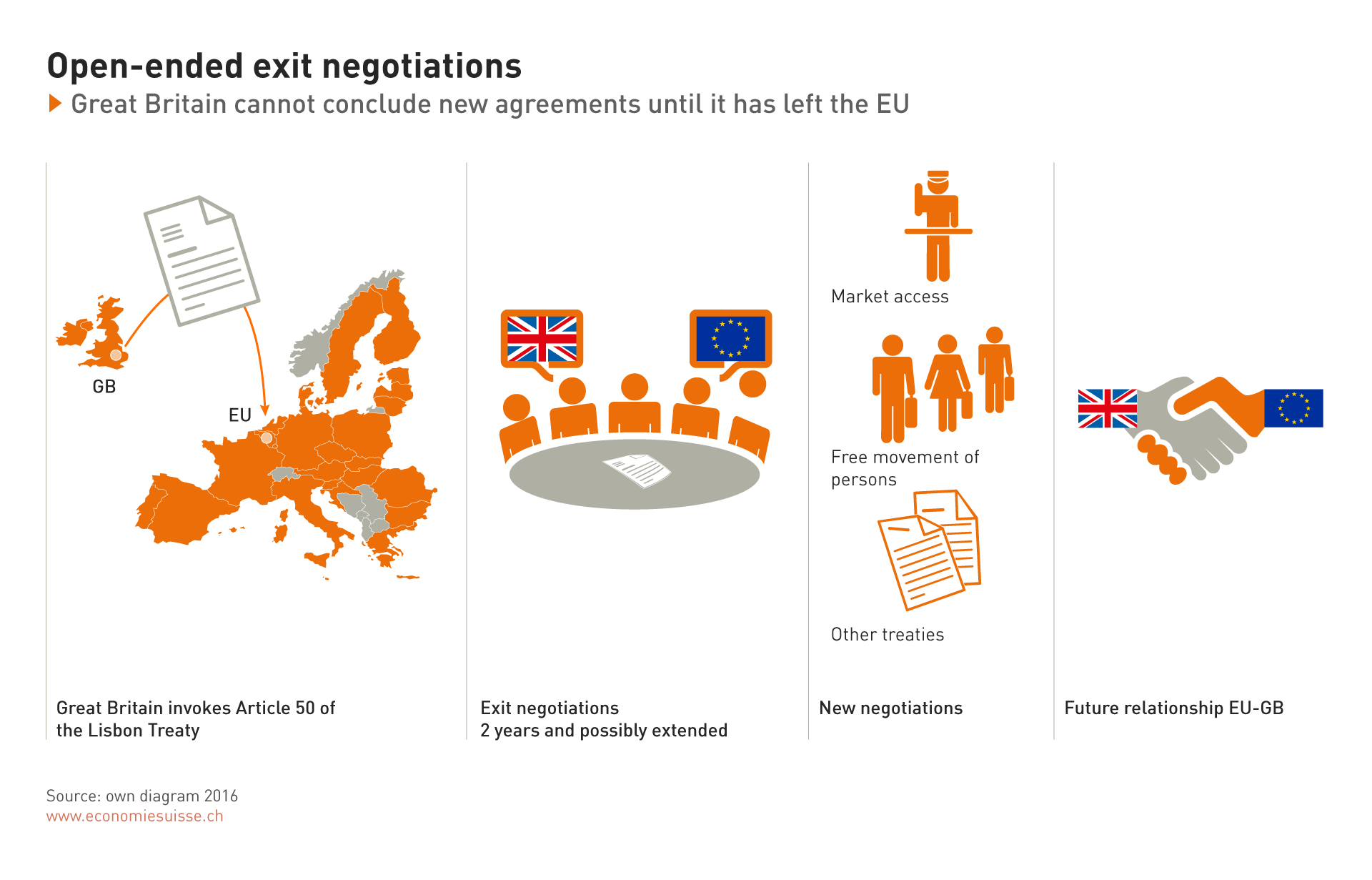

Unpredictable Withdrawal Negotiations

After the referendum of June 23, Article 50 of the Treaty of Lisbon will be activated for the first time ever—signaling the start of actual withdrawal negotiations. According to Article 50 „any member state may decide to withdraw from the Union in accordance with its own constitutional requirements“. To activate the withdrawal process the departing member notifies the European Council of its intention. Still unresolved is the question whether the British government needs a parliamentary decision in addition to the (formally consultative) referendum vote. The High Court confirmed this, but the government has appealed the decision. A Supreme Court decision in the matter is expected in January 2017. Once Article 50 has been activated there is basically no turning back. A deadline extension requires the unanimous agreement of all remaining EU members. The EU determines the guidelines for its negotiating position without the participation of Great Britain. This may involve decisions about the effective date of withdrawal or periods of transition, but also the future status of the UK (e.g. market access, free movement of persons, security, justice). The withdrawal agreement must be ratified by the British Parliament as well as at least 20 of the 27 remaining EU members and the European Parliament. In view of this, EU representatives already caution that the actual negotiating period may turn out to be shorter (until October 2018). Treaties covering the future relationship to Great Britain will require the approval of all remaining EU member states.

If no withdrawal agreement is achieved within the two-year deadline, Great Britain automatically leaves the EU without an agreement. In this case, foreign trade would have to return to existing WTO law and treaties concluded before the UK’s entry into the EU, which for the most part do not meet the today's requirements. For the economy such a scenario spells great legal uncertainty. More so, because according to the Treaty of Lisbon negotiations on the future relations between the two partners may not begin before Britain’s withdrawal

Chart 3

Failure to secure an exit agreement during the two-year negotiations means Great Britain is automatically excluded from the EU without an agreement of any kind.

Which Solution Will Great Britain and the EU Choose?

Even after a withdrawal the EU will remain Britain’s most important partner for the foreseeable future. So far neither Great Britain nor the EU have officially commented on concrete negotiation targets. Within the EU, views differ concerning the extent to which the UK should be accommodated. But everyone agrees how the four basic freedoms that come with access to the EU single market should be handled: the free movement of persons, goods, services, and capital are a unified package.

Even before the referendum of June 23, 2016, the British government presented and analyzed five possible scenarios although, realistically speaking, these are more like fairly generic "landing zones". None of the models discussed matches the full single market access that comes with EU membership. But negotiations are dynamic by nature. Who knows what new solutions or new combinations might suddenly emerge. However, the various options do offer some important clues regarding possible advantages and disadvantages of different landing zones (e.g. political sovereignty vs. market access). In any event, the short negotiation period and the looming legal insecurity in the event of a failure to reach any kind of agreement are huge challenges for both parties.

Five possible scenarios

Brexit as Game Changer?

The scenarios listed above do not take into account possible institutional changes in the EU. Yet considering the economic and political importance of Great Britain, EU reforms in the wake of Brexit are quite possible.

Inside and outside the EU different approaches are being discussed. Proposals range from the acceleration of existing projects to a fundamental overhaul of rights and obligations within the EU (e.g. continental partnership with different levels of integration and co-decision rights). If the EU actually commits to fundamental reforms the role of EFTA might be changed significantly — possibly with Great Britain as a member.