Switzerland and the United Kingdom: joint efforts for a prosperous future

- Introduction Executive summary | Positions of economiesuisse

- Chapter 1 The United Kingdom in Europe – one year after Brexit

- Chapter 2 Bilateral economic relations between Switzerland and the UK – taking stock

- Chapter 3 Calling for further deepening of relations with the UK

- Chapter 4 Growing together with bilateral networking

Bilateral economic relations between Switzerland and the UK – taking stock

Brexit and the conclusion of the EU-UK TCA also put Switzerland under pressure to act in two respects: on the one hand, bilateral relations with the United Kingdom had to be placed on a completely new contractual basis within the shortest possible time as part of the ‘mind the gap’ strategy. This was because the bilateral treaties with the EU were no longer applicable to bilateral relations between Switzerland and the UK at the time of Brexit. On the other hand, with a view to the EU-UK TCA, it is necessary to address possible discrimination potentials of Switzerland vis-à-vis the EU in the relationship with the United Kingdom.

CH-UK: declining goods trade, increasing trade in services and investments

The United Kingdom is Switzerland’s third most important economic partner after the EU-27 countries as a trading bloc and the USA. Conversely, Switzerland is also an extremely important trading partner for the UK. Neither Brexit nor the coronavirus pandemic have changed anything about the UK’s relative importance for Switzerland. This manifests itself in a bilateral trade volume of over CHF 35 billion (goods and services, excluding gold, 2020).

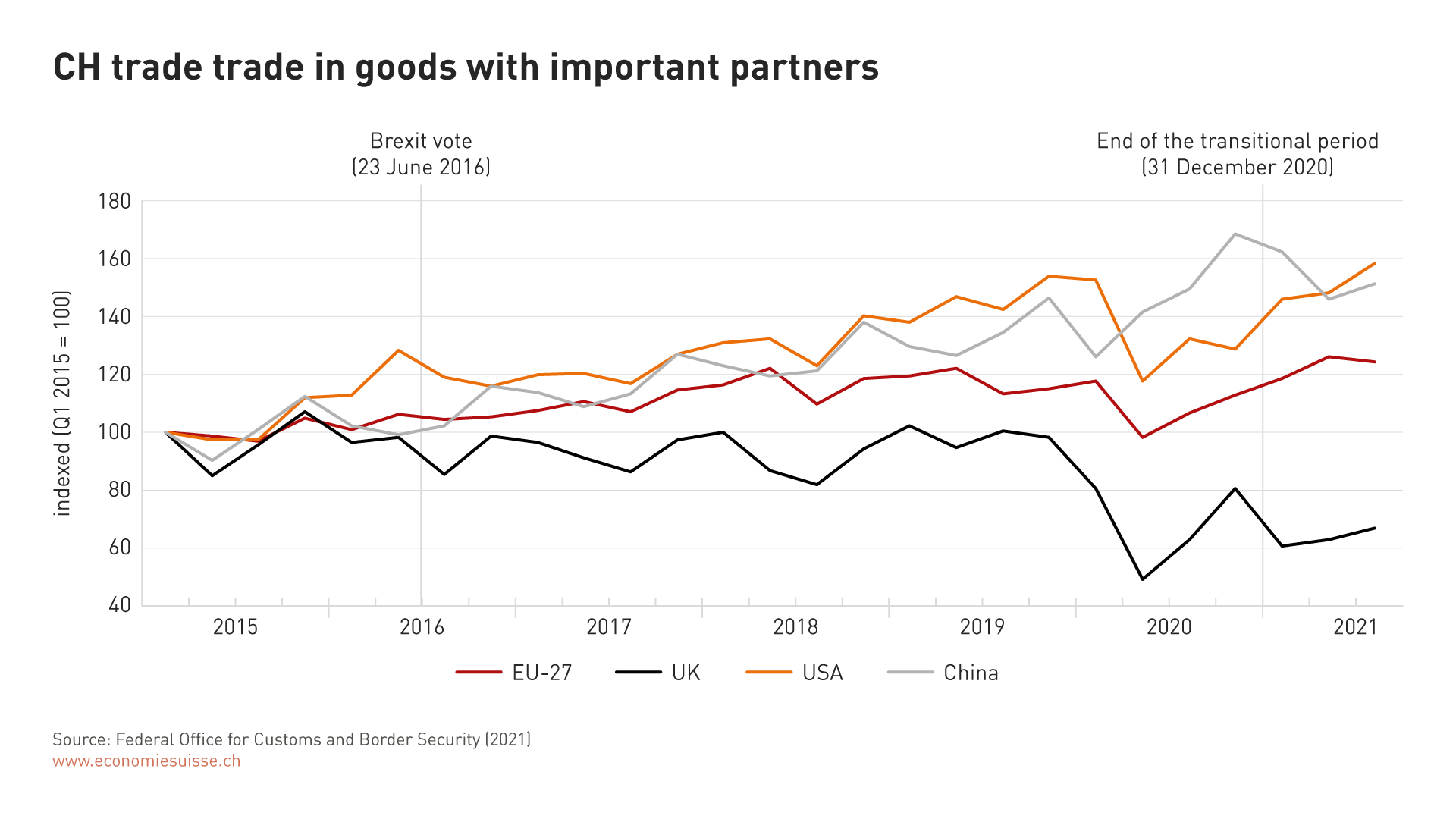

Nevertheless, with regard to other important partners, it can be seen that goods trade has tended to develop negatively compared to 2015: in the first three quarters of 2021, trade in goods with the EU-27 countries was 24.6 per cent higher than in 2015, while trade with the USA and China was even 52.9 and 57.3 per cent higher, respectively. In contrast, Switzerland’s goods trade volume with the United Kingdom fell by 31.8 per cent in the same period. All important Swiss export sectors were affected. Here, too, the strong increase in the last quarter of 2020 and the sharp drop in the first quarter of 2021 are striking. This confirms that the slump was not only caused by the coronavirus pandemic, but also to a large extent by the uncertainties of Brexit.

For the subsequent quarters of 2021, the pharmaceutical, chemical and watch industries showed a slight recovery, while the mechanical and electrical engineering, metal and textile industries continued their downward trend again after a brief upturn in Q2. As the UK’s border control regime has not yet been fully ramped up, it cannot be ruled out that further negative effects on bilateral goods trade dynamics could become visible in 2022.

The CH-UK bilateral trade in goods recorded a massive slump in 2021 and is recovering only slowly. Moreover, the control regime for goods imports at the British border will not be fully developed until 2022.

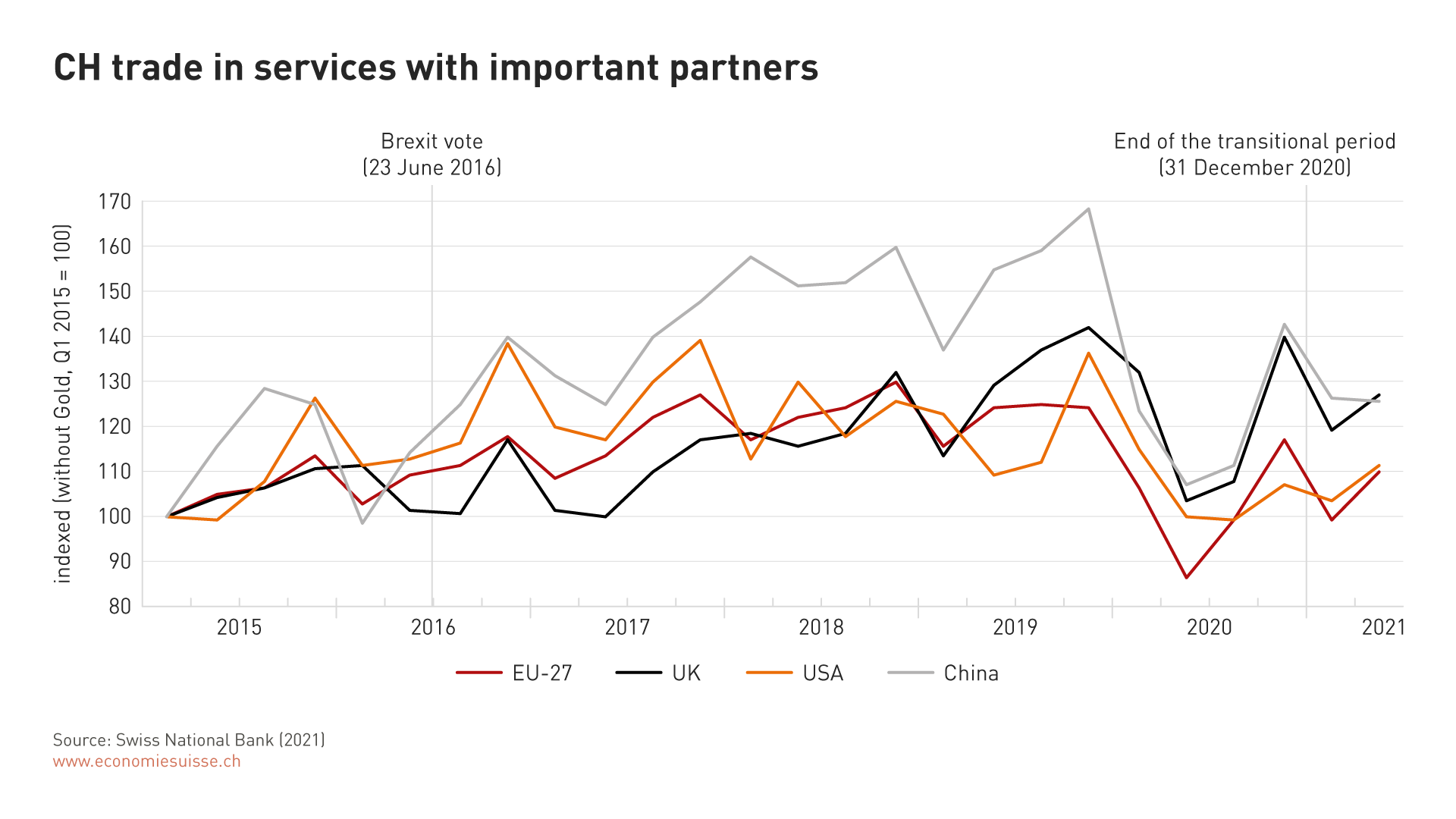

The United Kingdom also remains Switzerland’s third most important partner in services trade, behind the EU-27 states and the USA, and ahead of China. In contrast to goods, however, the development here is positive: a comparison of the first two quarters of 2015 and 2021 shows a significant increase in Switzerland’s trade in services with the United Kingdom (+21.1 per cent), whereas trade with the EU-27 countries increased much less (+2.2 per cent). The USA and China recorded an increase of 7.3 per cent and 16.7 per cent respectively in the same period.

For the years 2020 and 2021, the influence of the coronavirus pandemic, combined with drastic restrictions in the cross-border movement of persons, is likely to have had a much stronger impact than Brexit: the pandemic has led to a drastic decrease in cross-border mobility – with or without the free movement of persons. Only when the epidemiological situation returns to normal will it be possible to make a more meaningful statement about the effects of the loss of the free movement of persons in relation with the UK.

In contrast to goods trade CH-UK, a positive development has been observed in services since 2015. Restrictive Corona measures make it difficult to assess the loss of the free movement of persons in the context of Brexit.

The economic importance of the United Kingdom for Switzerland is also reflected in direct investment: with a capital stock of CHF 89.4 billion, the UK was the third most important target market for Swiss foreign direct investment in 2020, behind the EU-27 states and the USA. British direct investments in Switzerland amounted to CHF 62 billion in the same year.

The bilateral investment dynamics (capital stocks) from 2015 to 2020 with the United Kingdom clearly exceeded those with the EU-27 countries: investments from Switzerland to the UK (+93.2 per cent) almost tripled in relation to those to the EU-27 countries (+32.6 per cent), and the increase on the USA was even greater (+42.5 per cent). British investment stocks in Switzerland rose by 49.7 per cent in the same period. By comparison, investments from the EU-27 countries grew by 23.6 per cent over the same period, and those from the USA by 64.2 per cent. However, British investments in Switzerland have been declining again since 2018.

Member survey: Swiss business anticipates calming after initial turbulence

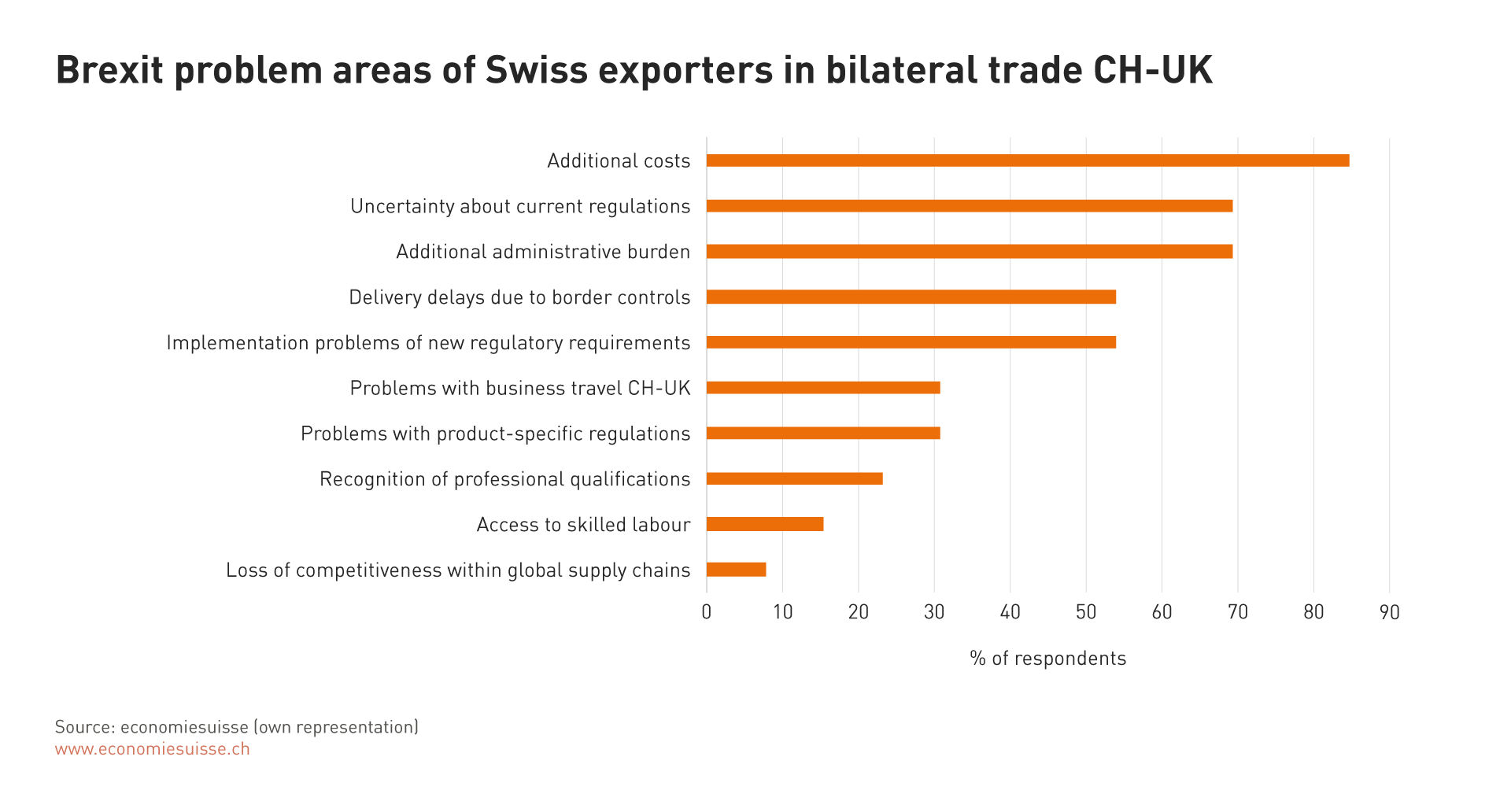

Due to Brexit, a large number of Swiss export companies were faced with considerable challenges in the short term. This is confirmed by a member survey conducted by economiesuisse (November 2021). The most frequently cited problems in bilateral CH-UK trade included additional financial and administrative burdens (e.g. customs duties), uncertainties about the rules to be applied when exporting and delivery delays due to lengthy border controls. But companies also reported difficulties in the area of mobility and access to skilled labour.

Brexit confronted Swiss exporters with major challenges. In the medium and long term, however, confident forecasts for bilateral economic relations prevail.

Despite these problems, economic operators expect bilateral trade and investment relations to stabilize soon. This optimistic picture is based on the fact that the initial turbulence was also caused by European companies’ and authorities’ lack of ‘routine’ in dealing with the new legal framework post-Brexit. On the company side, this adjustment process included changes to internal processes, delivery deadlines, production and logistics networks, as well as special staff assignments and regular contact with the authorities. In addition, Switzerland and the United Kingdom were also able to address problems at the political level. Finally, the United Kingdom itself will also be able to clear up various uncertainties with a view to shaping future framework conditions.

However, for Swiss companies, the UK’s exit from the EU will inevitably be accompanied by new trade hurdles and additional costs for cross-border flows of goods and services in Europe (see chapter ‘A free trade agreement is not participation in the single market’). A recent survey by the German Chamber of Industry and Commerce among its member companies on the issue of Brexit came to similar conclusions.

Contractual status quo of CH-UK bilateral relations largely secured

The ‘mind the gap’ fallback solution between Switzerland and the United Kingdom comprises nine agreements that have been in force (partly on a provisional or temporary basis) since 1 January 2021. They concern trade, mobility of service providers, insurance, aviation, road transport, acquired rights of citizens, coordination of social security, police cooperation and customs procedures. In addition, the United Kingdom assures Switzerland that it will unilaterally guarantee all existing EU equivalence recognition in the financial services sector vis-à-vis Switzerland even after Brexit. This also includes Swiss stock exchange regulations, which the EU did no longer recognise as equivalent from 2019.

The Swiss business community was closely involved in the implementation of the ‘mind the gap’ strategy by the Federal Administration. In essence, these agreements and unilateral measures secure the status quo of CH-UK relations as far as possible. The existing gaps are also due to the fact that the United Kingdom is seeking greater regulatory autonomy vis-à-vis the EU through Brexit.

Compared to the situation before Brexit, Switzerland was unable to secure the status quo with the United Kingdom in the following four areas in particular:

- facilitation of entry and residence, but no continuation of the free movement of persons

- mutual recognition agreements (MRAs) in conformity assessments of industrial products for only three categories instead of the previous 20: vehicles, Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) and Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP)

- limited possibilities for cumulation in CH-UK trade with input materials from certain countries as a result of the UK’s withdrawal from the PEM Convention.

- additional border controls on trade in goods as a result of the UK’s withdrawal from the CH-EU Common Veterinary Area and the European Customs Facilitation and Security Agreement.

Preferential rules of origin in bilateral CH-UK trade

Due to differences in the content of the CH-UK rules of origin compared to the TCA EU-UK, cumulation1 with input materials originating in the EU was not possible in CH-UK trade at the beginning of 2021. As a result, British and Swiss exporters had to pay new customs duties. In order to enable cumulation with input materials originating in the EU, Switzerland and the United Kingdom agreed to adjust the bilateral rules of origin on 8 June 2021. Specifically, the revised rules of origin of the PEM Convention were incorporated into the CH-UK trade agreement as of 1 September 2021. This step removed a major obstacle to trade. The solution was preceded by an intensive but constructive exchange between the authorities and business representatives of both countries.

Despite the new agreement between Switzerland and the UK, other cumulation problems remain in the new relationship between the EU, UK and Switzerland and with other trading partners. These problems cannot be solved within the framework of the CH-UK bilateral relationship, but only with the involvement of all parties concerned.

1 Cumulation involves adding up the value added that takes place in different free trade partner countries in order to meet the criteria for tariff preferences.

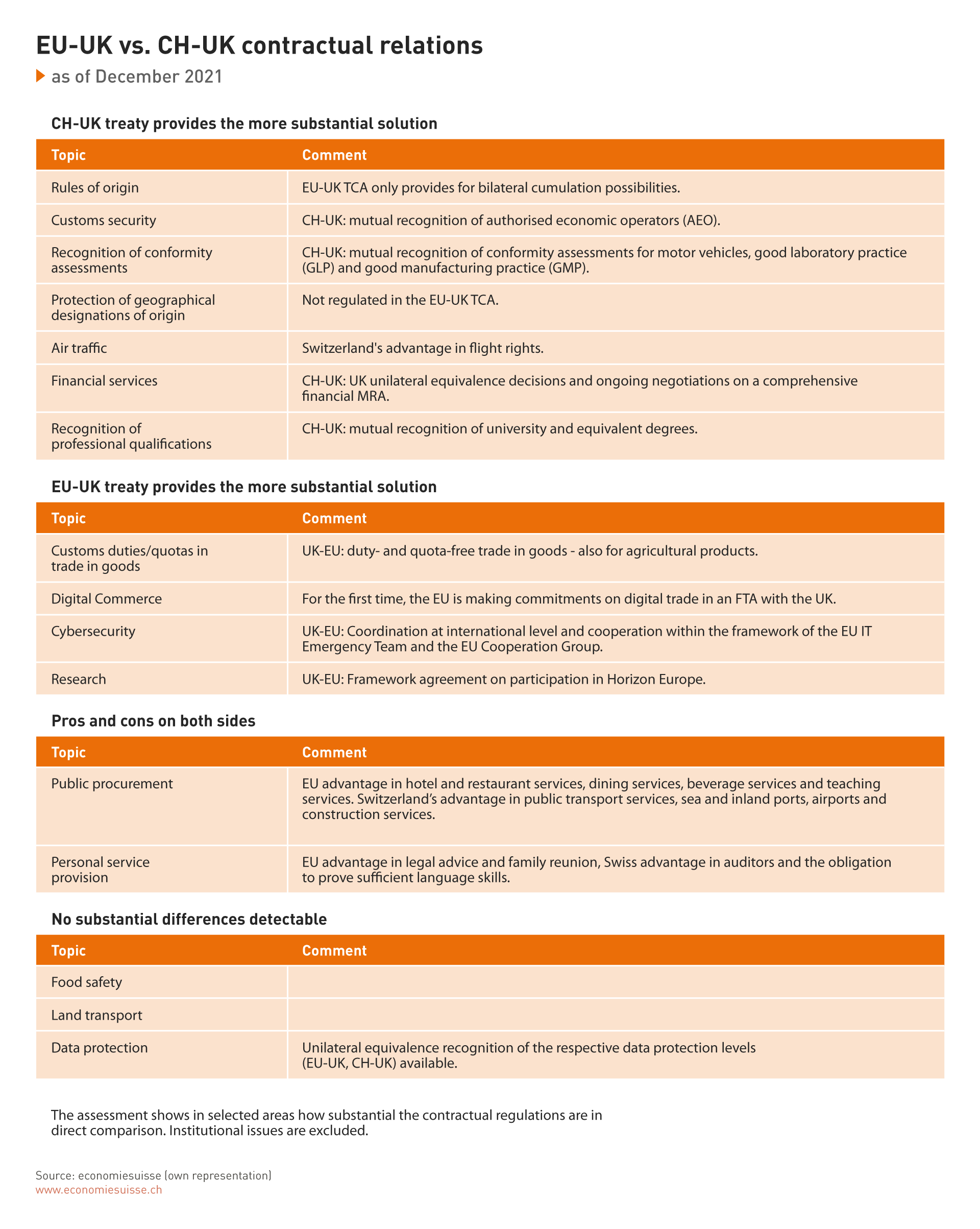

Addressing the potential for discrimination against the EU

The negotiations of the United Kingdom with the EU and Switzerland led in part to different results due to different interests. The parallelism of CH-UK and EU-UK negotiations as well as interdependencies in terms of content also played a role here. For Switzerland, the TCA EU-UK is particularly relevant in areas where the UK and the EU negotiated more far-reaching concessions than the UK and Switzerland.

A comparison of the UK's treaty relations with Switzerland and the EU reveals advantages for Swiss companies, but also potential for discrimination against EU competitors. These must be addressed.

The overall comparison shows that the bilateral treaty solution between Switzerland and the United Kingdom should be improved in some points in the medium term, despite its good substance. On the one hand, it is important to avoid discrimination vis-à-vis the EU (e.g. public procurement, provision of services or digital trade). On the other hand, however, there are also opportunities to go beyond the existing contractual agreements in the bilateral relationship and thus tap previously unused potential. These fields of action are to be addressed in the context of the planned deepening of the CH-UK trade agreement (see chapter ‘Lifting the bilateral trade agreement into the 21st century’).